What SSL does

SSL (Secure Socket Layer) is a is a public-key encryption system used by web sites, apps and email for protecting the data transferred between your web browser and the site you visit. SSL provides two things: it ensures that data in transit cannot be read by anyone intercepting it, and it also certifies that the site you are connecting to is who it says it is. SSL is typically used on login pages and when accessing anything secure, such as bank accounts, tax systems etc. It’s also a good idea for CRM systems since your CRM may contain personal information about your customers, and business information you’d prefer wasn’t public. Whenever you access your CRM system without SSL, everything you see (including your passwords!) is potentially readable by someone else without your knowledge. This is especially true if you use public WiFi or mobiles.

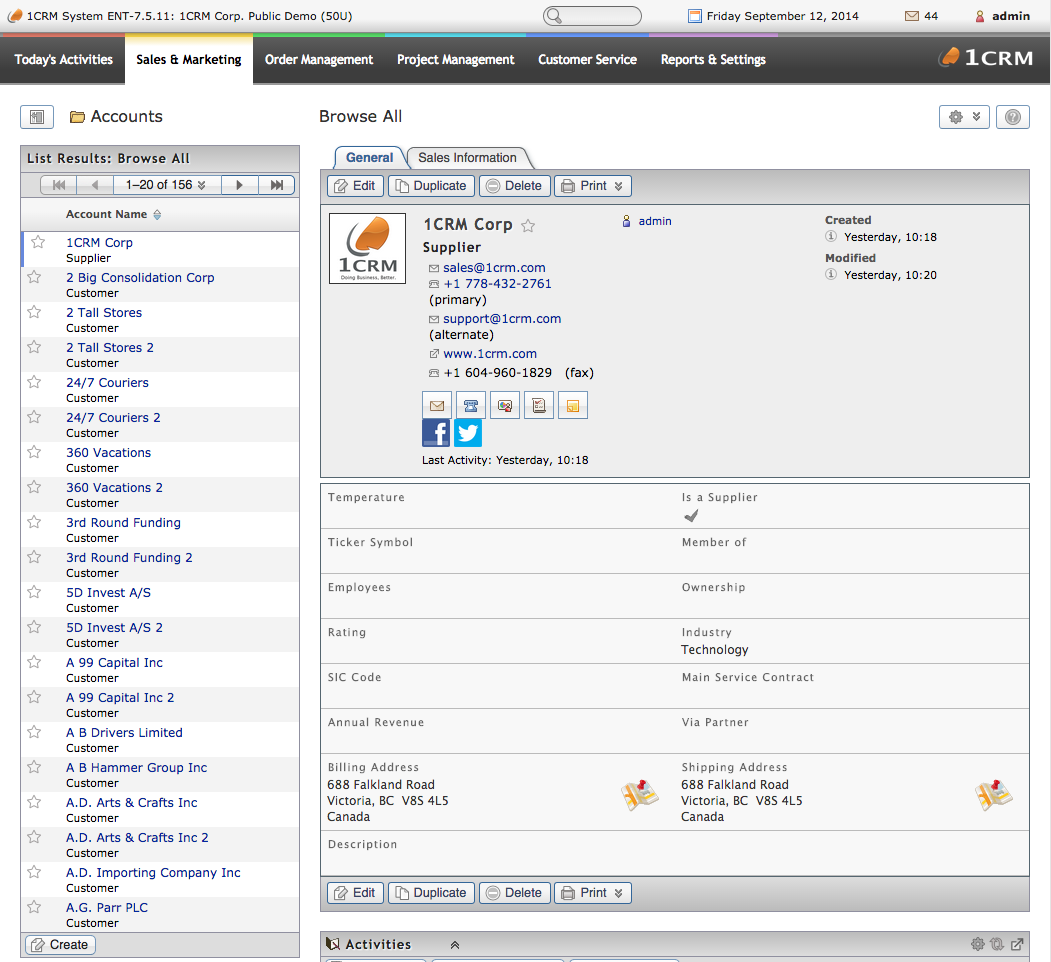

We provide an option for SSL on our 1CRM hosting, so we thought we would expand on what that involves, and what advantages it brings.

Getting SSL

SSL encryption involves two parts: a key and a certificate, sometimes called private key and public key. The certificate (signed with the private key) is presented to visitors to your site. They use it to encrypt data they send to you, which you can decode with your private key. In the other direction, you encrypt data with your private key that they can decrypt with the certificate. This mirror-image mechanism is called symmetric public key encryption. Fortunately, all this mathematical complexity is handled automatically by your browser, so you don’t need to do anything – it just works!

Getting your own SSL certificate involves several somewhat complex steps. First you need to generate a private key (with at least 2048 bits – see below), then you need to use that to generate a certificate signing request (CSR, signed with an SHA2 hash, see below) which is sent to a certifying authority (CA, an SSL certificate seller). The CA will then attempt to validate that you are who you say you are to varying degrees according to the rating or class of the certificate (in increasing rating: class1, class 2, class 3 and extended validation, or EV). When they are happy with that, they will generate the certificate and send it to you for you to deploy on your web site, email client etc. That all sounds complicated, but most CAs have simple processes and good documentation to help you through the process. Certificates are typically valid for 1 or 2 years.

We recommend gandi.net for SSL certificates (and many other things!), and startssl.com if you’re more technically minded and appreciate a radical approach to running a CA!

Our standard SSL service makes use of a class-2 wildcard certificate (which supports all hostnames within our syniah.com domain), which can be used without any action from you – we just need to enable it for your 1CRM installation. If you want to use your own domain and certificate, we can provide that option, though additional cost is involved, and please contact us before ordering your certificate!

Attacks on SSL

Because SSL is used to protect valuable data, it’s often the focus of attacks that try and break or otherwise circumvent what it’s doing. There have been two recent attacks on SSL that have made the news.

Heartbleed

The first of these was the terrible “Heartbleed” bug in OpenSSL (the most commonly used implementation of the SSL standard). This was addressed by fixes in OpenSSL which were then deployed to affected sites.

Like pretty much everyone else in the world, we were affected by this, and applied security patches as soon as they were available.

POODLE

A more recent vulnerability known as POODLE attacks the old SSL version 3 protocol. This mainly affects older browsers with poor security records, such as Microsoft Internet Explorer 6 since SSLv3 has been considered obsolete for some time. The SSL protocols have been superseded by the newer TLS (Transport Layer Security) protocols, and recent browsers support TLS 1.2, the latest and most secure version. The solution for this is to disable SSL version 2 and 3 support on the web server end, which prevents visitors from connecting with older, insecure browsers, but if you have an old browser and you visit sites that have not updated their servers, your data may be intercepted. If you are using an old browser that does not support recent TLS versions, you really should upgrade – you will find that secure sites will increasingly refuse to serve you.

We had already disabled SSLv3 several months before the POODLE attack was revealed, so we have not had to make any changes. One effect of this policy is that our sites will not work on Internet Explorer 6 or 8 running on Windows XP. IE8 will work on newer Windows OSs (though you should be running at least IE10 anyway).

Certificate hashes

SHA1 is a secure hashing algorithm (similar to a checksum) that’s used in verifying/signing SSL certificates. SHA1 replaced the older MD5 algorithm, and before too long, SHA1 is going to need replacing too. It’s no great surprise that the replacement is called SHA2. The strength (resistance to tampering, likelihood of bad data resulting in a correct hash) of a hash is roughly proportional to its length, measured in bits. MD5 uses 128 bits, SHA1, 160, and SHA2 supports 224, 256, 384 and 512 bit variants, of which SHA256 is the most commonly encountered. While this is somewhat independent of SSL/TLS itself, the hashing function is important when used to sign SSL certificates. Some sites and browsers have started rejecting certificates signed with SHA1, and that trend will increase, so if you are obtaining a new SSL certificate, make sure you get one that’s signed using SHA2, though be warned that some CAs have not got as far as offering them yet!

Our certificates have SHA2 (SHA256) signatures.

Key length

Much like the SHA1 issue, SSL keys have a key length, and the longer it is, the more secure the key. At present 1024-bit keys are common, but, like SHA1, these are likely to prove insufficiently secure in the near future, so although 1024-bit keys are OK for now, you should ensure that the keys used to sign any new SSL certificates are 2048 bits long. You can create 4096-bit keys, but the improvement in security is mostly academic and it will slow down encrypted connections.

Our certificates use 2048-bit keys.

Improving security by default

A recent security enhancement for web sites is the HTTP Strict-Transport-Security header, known as HSTS. This says, to browsers that understand it, that all traffic to the site should be encrypted, and your browser remembers that it has seen this setting and uses it by default in future visits. A usual pattern for secure sites is that you may first visit an unsecured URL (like http://www.example.com/), and your browser is redirected to the secure site (https://www.example.com/). This is good, but it takes additional time to load the first page, which may be significant on mobile devices. If you have visited a site with HSTS enabled, the next time you go there it will skip the first, unsecured, request and go straight to the secure version of the page. This applies to the entire site – so if you have visited the home page before, but later go to some other page, your browser will still automatically assume that it should use encryption. It also helps avoid a “mixed security mode” problem – it’s possible to have a secure page that loads other elements (e.g. images) from unsecured URLs in the same domain (though it won’t touch those on other domains, so it’s not a complete solution). Most browsers will complain or show some kind of warning (IE is particularly ‘noisy’!) in this case. If HSTS is set, these elements are automatically requested from secure URLs, even if the page doesn’t tell them to. So if a secure page loads an image from http://www.example.com/myimage.jpg, the browser will automatically convert it to the secure https equivalent at https://www.example.com/myimage.jpg, thus avoiding the mixed security mode warnings.

HSTS is set (with a long expiry) on all the 1CRM sites we serve over SSL, and this site too.

Testing SSL

There are many variables involved with providing SSL service, and they can have an impact on speed and security. Rather than guessing what it’s going to do, it’s much easier if you can test common configurations. Security vendor Qualys has a great SSL testing service you can use to assess your SSL configuration – you can point it any SSL site and see what it’s doing – try your bank! While you might want to score 100 in all categories, the only way to do that is to block access to older browsers that don’t have support for the stronger encryption mechanisms, so you need to balance the encryption options against browser compatibility, which fortunately is easy to do with the Qualys report.

We score an A+ on Qualys’ tests, their highest rating.

Improve your search ranking

There’s a rather surprising bonus to implementing SSL on your site: Google will consider it in your page rank, so having SSL can improve your search results placing.

Improve performance

This is perhaps the most unexpected payoff. Traditionally, SSL has been avoided because it imposes an additional layer of network activity on every request, and takes additional processing time on both browser and server. Two things have changed: computers are now so much faster that the processing overhead is negligible, and Google invented SPDY. SPDY (pronounced “Speedy”) is an enhancement to HTTP, the protocol used to transfer nearly all web content. SPDY provides some useful improvements – where a page refers to multiple items (e.g. images, scripts) from the same location, it can fetch them in a single request, instead of having to make a separate request for each one. It also applies compression to the headers that accompany most HTTP traffic. These two together (and various other smaller improvements) mean that SPDY can be considerably quicker than traditional HTTP. But here’s the big thing: it only works over SSL. SPDY is supported by most popular web servers (apache, nginx), and (as of today, when Safari 8 finally joins the SPDY family in Mac OS X 10.10 Yosemite) all current versions of popular browsers. It’s backward-compatible too, so older browsers that don’t support SPDY will simply fall back to conventional HTTP+SSL.

We have been serving secure traffic over SPDY since 2012, when Google started using it on their home page.

TL;DR

Create any new SSL certificates using 2048-bit keys and SHA2 signatures. Enable the HTTP Strict-Transport-Security header and set up a redirect from your insecure site to the secure one. Configure your server with SSL options that get you a good score on Qualys’ SSL tester, balanced against browser compatibility. Enble SPDY on your web server, and upgrade your browser to one that supports it. Do all that and you’ll benefit from improved security, performance, and search ranking – what’s not to like?!

Alternatively, ask us and we’ll take care of it all for you.